Johnny Depp is “a wife-beater”. This is the verdict of the UK courts. Just writing that sentence feels genuinely shocking, and yet, by now perhaps, it should not. For a start, the allegation that he was physically abusive to his ex-wife Amber Heard emerged more than four years ago, after she applied for a temporary restraining order against him following their divorce, citing domestic abuse. It should also not be a shock, given how many other hugely famous men have been accused of abusing women.

Sean Connery was alleged to have beaten his first wife and frequently defended hitting women. His death this weekend sparked online arguments about how much the coverage should focus on the professional achievements of a man who repeatedly insisted it was fine to hit women, “if the woman is a bitch, or hysterical, or bloody-minded continually”, as he said in 1965.

But Depp is a very different figure from Connery. The latter represented alpha masculinity and aggressive sexuality. No one ever said it explicitly, but Connery’s defences for beating women fit in, on some level, with his image, and so that side of him was never going to be a problem with his audience.

Depp, however, represented something else. He sued the Sun for defamation when it described him as “a wife-beater”, something Connery would never have done, and it’s why for a certain kind of fan (me), this feels like the death of yet another childhood hero.

And yet, unlike the ends of Kurt Cobain and River Phoenix, perhaps you couldn’t describe this one as a shock. After the judge gave his verdict on Monday morning, Depp’s notoriously virulent online followers (a different kind of fan) made sure they got the predictable hashtags trending, all proclaiming Depp’s innocence.

I often wonder about these online Depp fans, given that they are most likely in their 30s and 40s. Such online stanning from the middle-aged is unusual, and yet that it is Depp who inspires it says a lot about him: both what he represented to my generation, and how far he has fallen.

Depp may appeal. “The judgment is so flawed that it would be ridiculous for Mr Depp not to appeal this decision, ” said a solicitor at the London law firm of Schillings, which represented Depp.

Depp with Amber Heard in 2015.

But by now, most of the world has seen the photos of Heard’s bruised face, and the court case presented a relationship that had become gruesomely toxic. The court heard recordings of Heard verbally abusing Depp and admitting to “clocking” him and throwing pots and pans at him.

But none of that could change the fact that the judge, Mr Justice Nicol, found the majority of Heard’s allegations that Depp abused her proved to the civil standard, and that, therefore, the Sun was entitled to describe him as a “wife-beater”.

It was always risky for Depp to pursue this case. Next year in the US he has a $50m (£38m) defamation case against Heard regarding an opinion piece she wrote about being the victim of domestic abuse; the verdict of this case will surely have some impact on the next one.

But it’s not just the judge’s verdict that has decimated Depp’s reputation. For a while, his life has been absurdly over the top: when he was asked in 2018 if it was true, as his managers alleged, that he spent $30,000 a month on wine, he replied that this was “insulting … because it was far more”.

So testimonies about private jets, cocaine for breakfast and arguments over – in perhaps the most memorable part of the trial – whether Heard or her yorkshire terrier had defecated in Depp’s bed were titillating, but little more.

More destructive to Depp’s career, and more dismaying to those who have followed him from the early days, was seeing how low he had fallen: throwing phones at his wife’s head; zonked out and covered in ice-cream; so riddled with jealousy of Heard’s male co-stars he referred to Leonardo DiCaprio as “pumpkin head” and Channing Tatum as “potato head”; sending vicious emails and texts to friends about Heard in which he referred to her as a “flappy fish market”.

Aside from everything else, Depp had always been unusually eloquent for an A-lister, with a courtly, old-fashioned conversational style. That was part of his appeal; now he was lobbing insults like a six-year-old. Somewhere, amid all the drugs and the drink, Depp seemed to lose his mind.

As I looked at the photos of him, turning up to court looking like a self-parody in his perma-present piratical scarf and blue-tinted sunglasses, to argue over whether it was human or terrier excrement in his bed, I felt horrified, of course, but I also felt sad. This was not how it was supposed to go. To those watching, the verdict felt inevitable, Depp’s trajectory less so.

For those who came of age in the 90s, Depp represented a different way of being famous. He complicated the narrative. Along with Phoenix and Keanu Reeves, he was part of a holy trinity of grunge heart-throbs. They were the opposite of the Beverly Hills 90210 boys, or Brad Pitt and DiCaprio, because they seemed embarrassed by their looks, even resentful of them. (Depp reportedly turned down Pitt’s cheesecake role in Thelma & Louise.)

This uninterest in their own prettiness made them seem edgy, even while their prettiness softened that edge. They signified not just a different kind of celebrity, but a different kind of masculinity: desirable but gentle, manly but girlish. Depp in particular was the cool pinup it was safe to like, and the safe pinup it was cool to like.

We fans understood that there was more to Depp, Phoenix and Reeves than handsomeness. They were artistic – they had bands! – and they thought really big thoughts, which they would ramble on about confusingly in interviews. If we dated them, we understood that our role would be to understand their souls.

He would never put it like this, but Depp cultivated this image. He decided almost from the start that he didn’t want to be just a celebrity but a cultural figure. In 1987, he was cast in Fox’s teen cops show 21 Jump Street, and at first he gave enthusiastic interviews about how much he enjoyed his “clean” and “slick” character, Tom Hanson.

But he soon appeared to realise he wanted more and regularly derided the show as “borderline fascist”, mentioning his own youthful drug experiences and how he lost his virginity at 13.

Nevertheless, 21 Jump Street was a huge hit, largely thanks to Depp. Sunday evenings for me, growing up in the US, quickly became about watching Depp bust some drug-dealing adolescents. But there were reports from the set that he would refuse to do scenes, leading to him getting a reputation as difficult, but to us fans this just proved that he had an artistic soul and was better than the TV show (although we also loved the TV show).

They paid him $45,000 an episode to make him stay – a dream for a poor boy from Kentucky, the youngest child of a waitress, who had lived in more than 20 different places before he was seven and whose parents divorced when he was a teenager.

But to Depp it was hell. “Lost, shoved down the gullets of America as a young Republican TV boy, heart-throb, teen idol, teen hunk. Plastered, postered, postured, patented, painted, plastic!! Novelty boy, franchise boy. Fucked and plucked with no escape from this nightmare,” he wrote about the show.

Depp was supposed to be a teen idol, but he complicated the narrative by choosing John Waters’ Cry-Baby for his big movie lead debut, kitschily satirising his image as a heart-throb, and spiking any producers’ attempts to pigeonhole him as just another pinup. In his next role, as Edward Scissorhands, he went further, entirely obscuring his good looks – not even James Dean did that – and relying instead on subtlety and acting skills, neither of which had been in much evidence on 21 Jump Street.

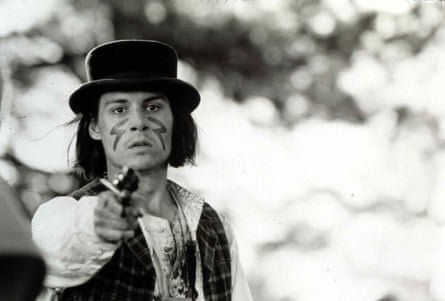

But he was good, or certainly good enough, and in the 90s Depp carved out one of the more interesting careers a teen pinup has ever managed. He worked with Lasse Hallström in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?, Jim Jarmusch in Dead Man, Roman Polanski in Ninth Gate and Mike Newell on Donnie Brasco (in which he probably gave his best performance).

And he took his audience with him; a whole generation discovered indie films and auteurs through Depp. He was that rarest of things: a celebrity who was, genuinely, cool.

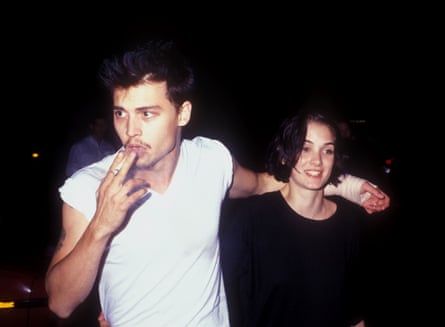

He was also known as a romantic. He was married briefly at 20, then developed a proposal habit, getting engaged to Sherilyn Fenn, Jennifer Grey and Winona Ryder, whose name he had tattooed on his arm: “Winona Forever” (changed to “Wino Forever”, when the booze lasted longer than the relationship. Similarly, he had “Slim” tattooed on his hand for Heard; after their divorce, he changed it to “scum”, then to “scam”).

With Winona Ryder in 1990.

We Depp fans loved Ryder. They made sense as a couple and, with her delicate gothic looks, she confirmed our image of him as a friend of the outsider (as though a gorgeous Hollywood actress could ever really be considered an outsider).

We were less pleased when he started dating a model, which felt a bit lame, but at least it was Kate Moss, and at least she seemed absolutely bananas about him, clutching his arm on the Cannes red carpet.

During their relationship, he notoriously tore up a hotel room they were staying in together, causing $8,000 worth of damage. But again, we told ourselves, this was just his artistic nature. And it was the 90s – destroying hotel rooms was what male celebrities did, right?

While Phoenix tended to come across as quite surly in interviews, and Reeves was monosyllabic to the point of incomprehensibility, back in the 90s Depp seemed more fun. Onscreen, he had a tenderness the others didn’t; off-screen, journalists loved him, and he would drive them around LA talking gnomically about his love life and showing them cool tricks he could do with a cigarette.

In the 90s, loving Depp was as uncontroversial as liking chocolate, and yet, unusually, the universality of appeal only added to his credibility. He had Oscar nominations and was the highest-paid star in the world. And yet, unlike any other actor who has achieved that – Jimmy Stewart, Tom Hanks – he was still cool. Back then, everyone loved Johnny.

Directors loved him, too, especially Burton, of course, but also Waters and Jarmusch. When I tried to talk to people he worked with for this piece before the judgment, they all said no because they wanted to protect him. Until very recently, he had a reputation for being one of the easier actors to work with, praised by the cast and crew of his movies for his professionalism and friendliness.

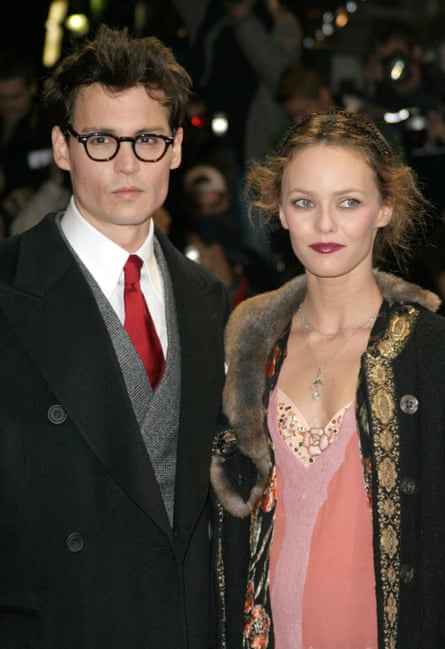

After he and Moss broke up, he got together with Vanessa Paradis, and they had two children, Lily-Rose and Jack. During their 14-year relationship, Depp, true to form, was positively uxorious about Paradis, praising her beauty and becoming a Francophile, giving interviews in French magazines about how much he loved the country.

France, he said to the magazine VSD in 2010, “has given me everything. A marvellous family and also an equilibrium which I missed enormously.” For a while, it looked as if Depp had gamed the celebrity system: he had found a way to be entirely true to himself while still being an A-lister and living a life of peace and contentment.

With Vanessa Paradis in 2004.

Depp had always approached fame with a very clear template. Among his 90s cohort, Phoenix struggled to match up his personal values with being a Hollywood actor, and Reeves didn’t appear to give the matter an enormous amount of thought beyond just doing what he wanted to do. But as early as 1990, Depp had settled on heroes he would namecheck in interviews: Iggy Pop, Marlon Brando, Keith Richards, Hunter S Thompson.

Thirty years later he would still be talking about all of them; he is, really, the ultimate fanboy. His Captain Jack Sparrow in The Pirates of the Caribbean is a pastiche of Richards, while Depp has made himself the keeper of Thompson’s flame, playing him in 1998’s Fear and Loathing in Los Vegas, and then posthumously bringing Thompson’s novel The Rum Diary to screen in 2011.

It was on this film set that he met Heard. Richards even had a small role in Depp’s court case. In a photo taken by Heard to show the extent of Depp’s drug use, the court saw cocaine lines laid out on the table, pirate-themed box of drugs nearby with the initials JD engraved on it, and there, in the background, a solo CD by Richards. If this had been an episode of Through the Keyhole, the mystery of to whom this table belonged would have been solved in the opening credits.

On the one hand, for a man to have the same heroes at 57 as he did at 21 would seem to prove the old adage that the age you become famous is the age you stop growing. (Depp also proves another old adage: never trust a man over 30 who reveres Hunter S Thompson.) On the other, it could also be seen as a testament to Depp’s consistency, even his authenticity. Whereas most actors pick up causes and side interests the way other people go through takeaway sandwiches, Depp has been enduringly faithful to his original loves.

Throughout his career, he sought out friendships with Richards, Thompson, Brando and Allen Ginsberg, which gave him a reflected retro sheen. He seemed to be from the past, his LA a grubby 50s version, as opposed to the glitzy 90s one in which he lived.

In a 2011 interview with Patti Smith in Vanity Fair, she asked him about his “mentors”, and he described them, enviously, as coming from “a radically different era … I really believe that, at a certain point, if you’re born in 60-something or whatever, you got ripped off – you know what I mean? I always felt like I was meant to have been born in another era, another time.”

Depp tried to bring the spirit of that era to his world, opening The Viper Room nightclub on Sunset Boulevard in 1993. That year, Phoenix collapsed and died outside it from an overdose.

In 2012, Depp announced he and Paradis were separating, and he was now dating Heard. Within a year, the once most famously romantic of Hollywood stars was sending text messages to his friend, the actor Paul Bettany, about Heard in which he said: “Let’s drown her before we burn her!!! I will fuck her burnt corpse afterwards to make sure she is dead.” When asked about the message in court, Depp said it was regarding a fight he had recently had with Heard: “She didn’t like me using alcohol and drugs because she had some delusional idea that they turned me into this said monster.”

His reputation for professionalism started to crack. He delayed the shooting of the fifth Pirates of the Caribbean film because of what he said was a hand injury – which Heard claimed in court occurred when he punched a wall during one of their fights – and there were reports from that set that Depp was drinking heavily and needed to have his lines fed to him through an earpiece. Depp did not deny needing an earpiece, saying it helped him “to act with his eyes”.

In Dead Man.

There has already been much discussion about how all of this will affect Depp’s career, and the answer depends on whom you ask. But probably one of the better clues came from Jerry Bruckheimer, who produces the Pirates franchise. When asked in an interview in May if Depp would be in the next Pirates film he replied: “We’re not quite sure what Johnny’s role is going to be. So, we’re going to have to wait and see.”

It has been a long time now since Depp was cool. The photos of him in London during the case, wearing a Rasta hat and matching striped T-shirt, brought a sad pang for those old enough to remember when he was the most stylish man in the world.

His last genuinely good film was Sweeney Todd in 2007, and he has spent the past few years making turkeys such as Lone Ranger, The Tourist and a genuinely unbearable cologne advert. His loyal fans would say that it all went wrong when he left Paradis for Heard in 2012.

And it’s true, leaving the mother of his children for a young blonde would have once, long ago, been beneath him. But it feels that the rot started before that.

According to his former management company, he was spending more than $2m a month, aided in no small part by the fact he cashed out to star in the Pirates franchise and was, for a time, earning more than $50m per role.

Even he called it “stupid money”, but insisted he was only demanding that price tag for the sake of his kids. His life quickly became absurd. In 2009, Vanity Fair ran what, in retrospect, looks like the tipping point piece, in which the writer described what it was like travelling on Depp’s carefully designed boat (“Orient Express by way of Parisian brothel”) to his private Caribbean island.

The whole thing is grotesquely over the top and crassly predictable, with Depp wanging on (and on and on) about Thompson and Richards, and sharing the advice Brando gave him about how to buy an island. “Money doesn’t buy you happiness. But it buys you a big enough yacht to sail right up to it,” he declares.

But if he was merely working to earn money for his children, that has all come to naught: in 2018 he told journalists that his fortune of $650m was gone. He insisted that his former managers had stolen millions from him; they claimed he had spent it. A $25m law suit between them was settled – the terms of the agreement were confidential – but that he had $650m to steal tells its own story. Who, really, can maintain any sense of reality when they are dealing with those sums of money? Maybe some people, but not fiftysomethings who idolise Hunter S Thompson.

Depp made the classic fanboy mistake of focusing only on the glamorous, external trappings of his heroes. He views Richards et al as eternal rock’n’roll figures, and constantly retells anecdotes from their hellraiser years.

But all of them wrestled with the question of how hellraisers deal with getting older in a way that Depp, apparently, has not. Richards quit hard drugs in 1977 and Iggy Pop also cleaned up long ago. Thompson killed himself at 67, ground down by poor health and depression; Brando ended up a bloated mess.

Depp could easily have grown into a figure like Richards or Iggy Pop: clean, cool, critically acclaimed, a revered cultural figure. Instead, in the past few years, it has become clear he has chosen the other option.

It’s sad, and it didn’t have to be this way. Of course that’s true of any celebrity downfall – any personal downfall – but with Depp, it felt like a different path was always there in front of him, in touching distance.

That now feels like an alternative universe. It would be easy to dismiss this as yet another spoilt, obnoxious celebrity shown up for being spoilt and obnoxious – easy but wrong, because that would miss why Depp was so compelling for so long. Until the allegations of abuse emerged, the stories that came out about Depp were, by and large, notably nice. Kind, even.

There was the time he donated £1m to Great Ormond Street hospital after his daughter had been treated there, and then afterwards visited the sick children still in there and read them stories, and, even when his life started to be excessive, his good friends stayed loyal.

But over the past decade, things started to change. Where once he drove journalists around LA and France and regaled them with loquacious thoughts about life, his more recent encounters with the press have had the feeling of Kurtz barricading himself in the jungle.

In 2018, he gave an interview to Rolling Stone, ostensibly about how he lost all his money, and ended up keeping the journalist, Stephen Rodrick, with him for three days. Rodrick described him as “alternately hilarious, sly and incoherent”, with a “scared, hunted look about him”. “If his current life isn’t a perfect copy of Elvis Presley’s last days, it is a decent facsimile,” Rodrick wrote.

The real connection between Depp, Phoenix and Reeves was that they were all hyperconscious of not doing the predictable thing. But with Phoenix dead at 23 from an overdose, and Depp mired in divorce, drugs and legal hell, his reputation now destroyed, only Reeves, of all unlikely people, has avoided the wearily familiar templates.

Only fools expect consistency from celebrities (from anyone, really), but what feels so strange about Depp to fans is how much he seemed to change, and how quickly, when he had been so consistent for so long. Or maybe he was the consistent one, with his eternal reverence for Thompson and Brando, and we’re the fools for being surprised.

In any case, the photos shown in court of Depp passed out on hotel room floors confirmed what most of us already knew, and the judge’s verdict has carved it in stone: Depp has become a spent cliche. That was the one thing we thought he would never be. But once again, he complicated the narrative.