Keanu Reeves as Neo in The Matrix. Photo: ©Warner Bros/Courtesy Everett Collection

This article was originally published on February 8, 2019. It has been republished to mark the 25th Anniversary of The Matrix.

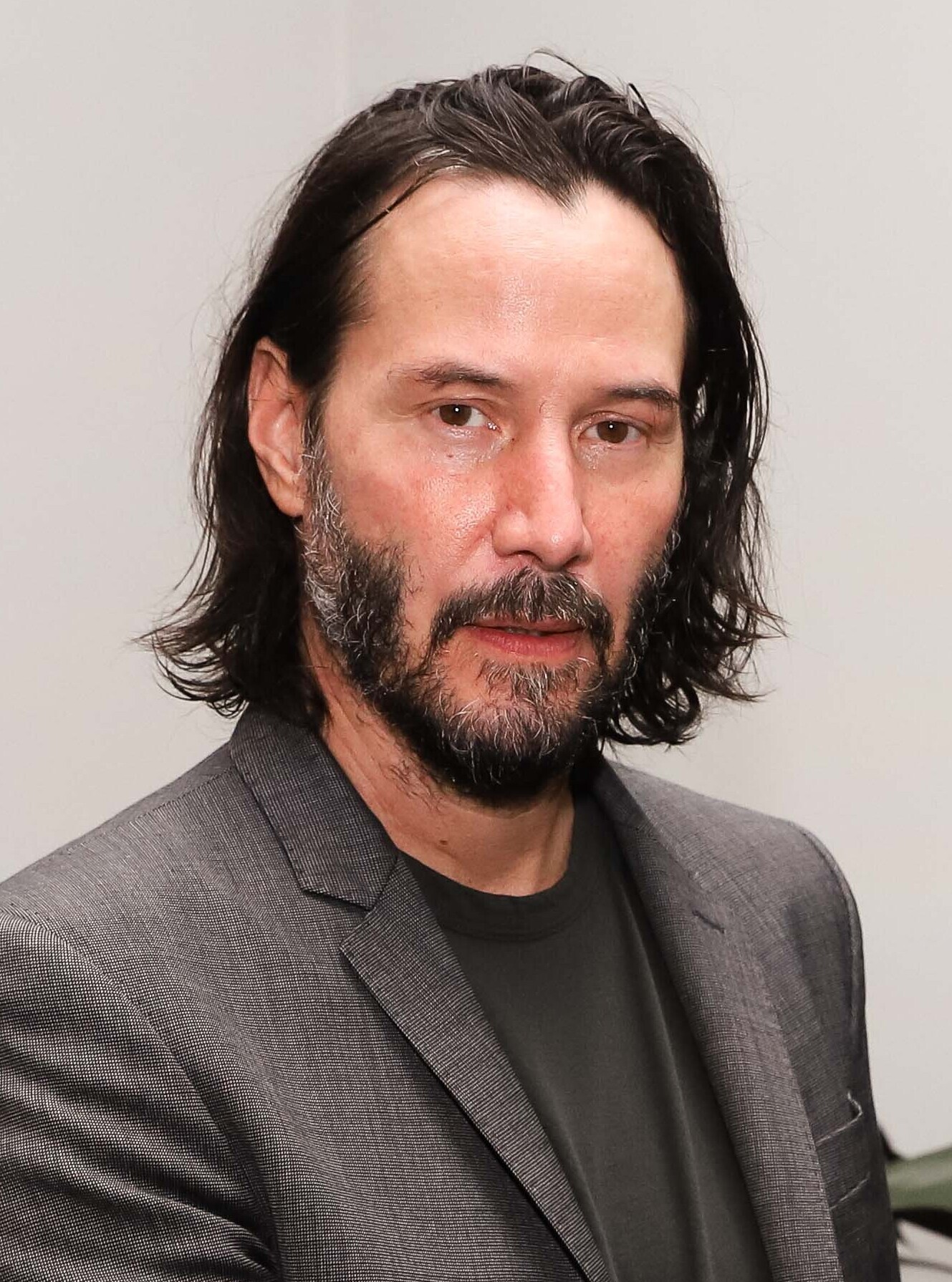

Throughout the 1990s Keanu Reeves created a form of action stardom that no other actor has quite achieved before or since — one predicated less on testing the limits of his body than on highlighting its beauty.

And 1999’s The Matrix marked the entrancing culmination of all he had been experimenting with during that decade.

Twenty-five years and three sequels later, it is hard to imagine anyone else but Reeves as Neo, the counterculture hacker turned savior. But before he came onboard, directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski considered several others, including Tom Cruise, Nicolas Cage, and Will Smith (who reportedly turned down the role so he could do the widely derided Wild Wild West, one of the greatest mistakes of his career).

These actors, at least at the time, hewed closer to a more traditional form of Hollywood machismo. But The Matrix is a film that operates on multiple levels: It’s a cyberthriller of unbridled intimacy, a scalpel-sharp action flick, a curious testament to optimism, and a still-worthwhile study of technology’s all-consuming power on our lives. It needs a lead who can operate on such levels as well.

As an action star, Reeves has repeatedly shown interest not just in the limits of the body and its raw strength, but also in its grace.

He isn’t like Tom Cruise, who pushes his body to ever-increasing extremes — leaping out of planes or onto the side of buildings with carefully calibrated aplomb. Nor does he possess the jokey charisma of a Will Smith.

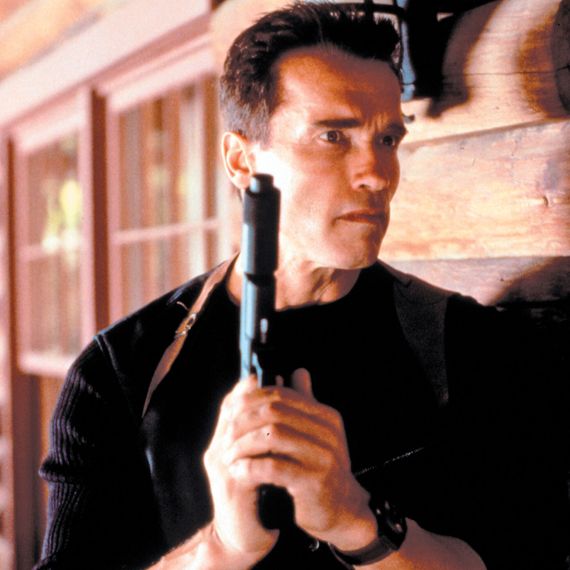

When we look at the most towering examples of Hollywood action stars — from the jaunty elegance of Errol Flynn, to the muscle-bound machismo of Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger, all the way down the line to the less distinct, glossy statesmen of the ever-expanding Marvel Cinematic Universe — Keanu Reeves remains an outlier.

For The Matrix, the Wachowskis coaxed a genuinely transcendent performance from Reeves, while also successfully synthesizing a host of inspirations (from cyberpunk literature to anime classics to various strains of philosophy detailing our notions of consciousness). The results profoundly rewrote the expectations of what an action star could be.

Neo’s mournful, curious gaze and joyful compulsion as he learns about the real world brought to the fore the idea that more soulful, willowy folks could carry a hidden lethality — a suggestion new to the American landscape, which often preferred its action stars’ powers conscripted to immensely muscled bodies, with true emotion either nowhere to be found or wrapped in slickly delivered sarcasm. Reeves suggested that an action star should feel, at full tilt.

In the wake of Neo’s slender poise, the notion of the “unlikely action star” became quite common. No longer did action films need to be anchored by chiseled, emotionally limited commandos like Stallone or martial arts experts with expressive charm like Wesley Snipes. An action star could be James McAvoy stumbling headlong into great power and various conspiracies in Wanted or pure maternal fury like Uma Thurman in Kill Bill I and II.

The saviors of a film could be as different as Michael Cera’s lanky, perennially awkward protagonist in Scott Pilgrim Versus the World and Matt Damon’s peripatetic amnesiac in The Bourne Identity and its sequels.

Think of Kate Beckinsale sauntering and slicing herself a bloody trail in gleaming latex in the Underworld franchise, or Reeves’s previous co-star Charlize Theron magnificently glaring her way through the wildly uneven Aeon Flux and the bombastic Atomic Blonde.

Pre-Neo (top row) and post-Neo. Photo: Warner Bros. Pictures/Photofest (Schwarzenegger); Columbia Pictures/Photofest (Van Damme); Double Negative/@Universal/Courtesy of Everett Collection (Cera); Columbia Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection (Macguire).

The melodramatic, FX-heavy superhero origin stories that proliferated throughout the 2000s also owe a huge debt to The Matrix.

The film’s entrancing FX showed Hollywood that any actor could be credible as an action star even if they had to do the impossible — flying into the starry night sky, leaping over buildings with ease, or dispatching various foes at such high speeds that their movements blurred, with nary a hair out of place.

You could even do it without the months of training Reeves and his co-stars put in to make their physical performances work all the more beautifully.

Even those action flicks that operate as portraits of hangdog, middle-aged men with unique sets of violent skills — think Liam Neeson’s Taken and its various imitators — are indebted to how Reeves opened new veins of emotion in the genre.

(Undoubtedly the most potent of this latter subgenre is Reeves’s own neon-soaked John Wick franchise.)

More striking though is how much The Matrix and its star influenced the internal lives of action leads going forward.

The “get the girl and save the world” model will always exist, but in the 20 years since The Matrix, the inner dimensions of our heroes have expanded. Unlike other action stars, Reeves’s masculinity is fluid, mutable.

He often suggests — with a smirk, or glare, or the careful precision of his balletic violence — that the emotional turmoil of his characters is more than just a plot point, but rather a physical reality interwoven into the performance. He’s one of the few male action stars who is also a gracious scene partner.

It’s more than just kindness; there’s a sense that he’s completely sure and secure in his own masculinity. It’s why he was able to play characters as disparate as Ted Logan in Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey and Scott Favor in My Own Private Idaho.

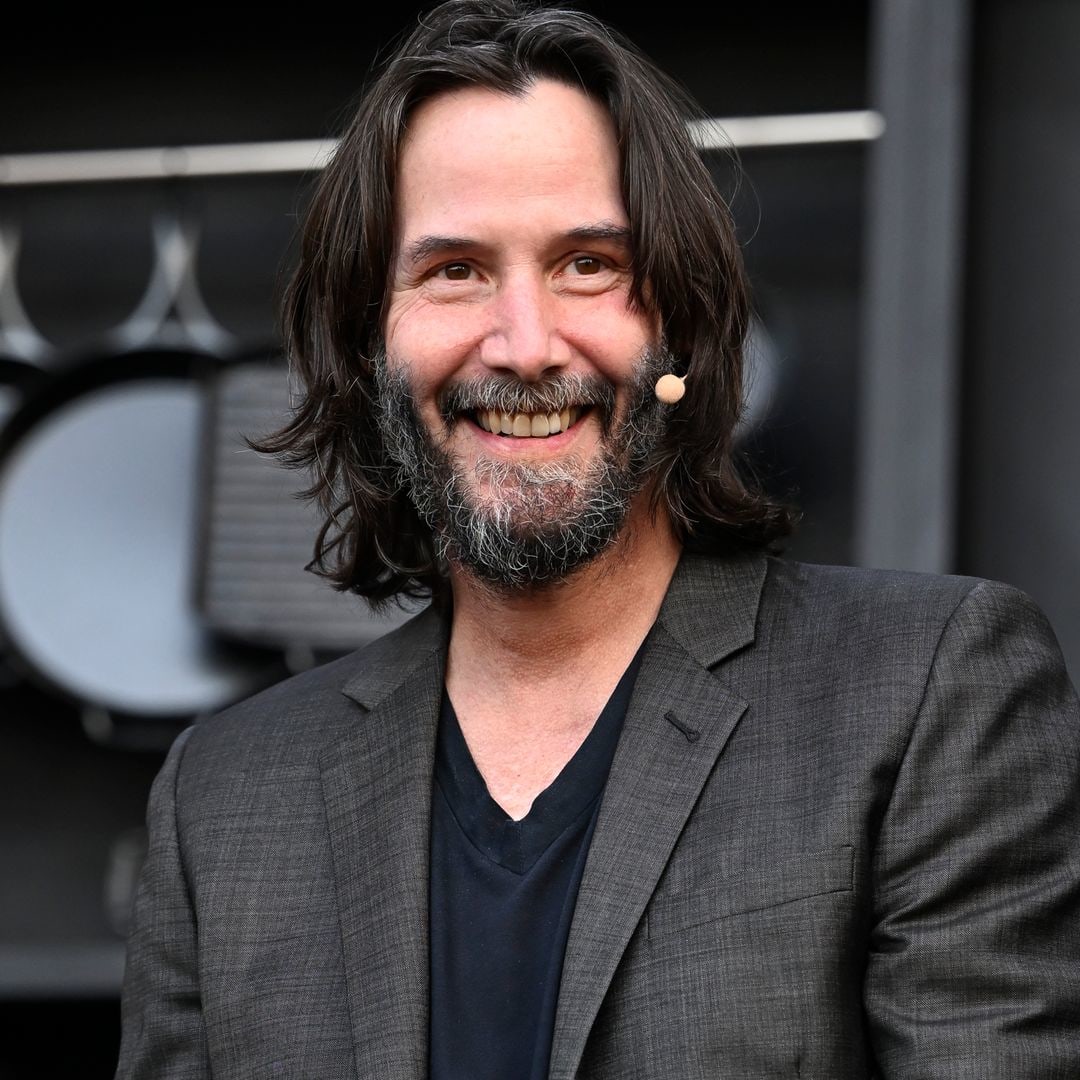

With Keanu, The Matrix takes on greater shades than merely being a propulsive, slickly engrossing blockbuster.

The way he foregrounds Neo’s curiosity and loneliness adds an untold dimension to the film, about what it means to find not just your purpose but your family as well.

Watch as he modulates this curiosity: around Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), it is tinged with the nascent twinge of lust; when he’s in Morpheus’s orbit, it is colored with awe.

The Matrix marries the actor’s interests, sensibilities, and background in ways that he would capitalize on in later work.

Reeves has British, Chinese, and Native Hawaiian ancestry, and his love of Hong Kong action flicks echoes in later works, like his directorial debut The Man of Tai Chi and the John Wick franchise.

With a star as vulnerable as Keanu, The Matrix avoids being a typical Chosen One narrative and instead becomes something more dynamic: a testament to our need for community.

As writer-directors, the Wachowskis carry a potent belief in humanity’s essential value. Whether through the sterile, machine-created world that we recognize as our own or the cataclysmic, gray future Neo finds himself navigating, they remind viewers that our bodies are things of beauty, to be molded, altered, and even transcended in order to reflect our inner desires and realities. Reeves doesn’t just reflect this, but complicates it as well.

Reeves has proven over the roughly 30 years of his acting career to be an essentially generous and curious performer with a near-beatific ability to be utterly present. This is often mistaken for a blank-slate quality. But he is far from blank.

He has a roiling inner life, from the moment we meet him in The Matrix — surrounded by the detritus of his largely digital existence and with Massive Attack slinking from his headphones.

As we watch him rebound from navigating a maze of cubicles with only the voice of a stranger as his guide to joyfully showcasing Yuen Woo-ping’s ecstatic fight choreography, we feel not only the wonder of this world the Wachowskis have created, but the joy of witnessing a star go supernova.