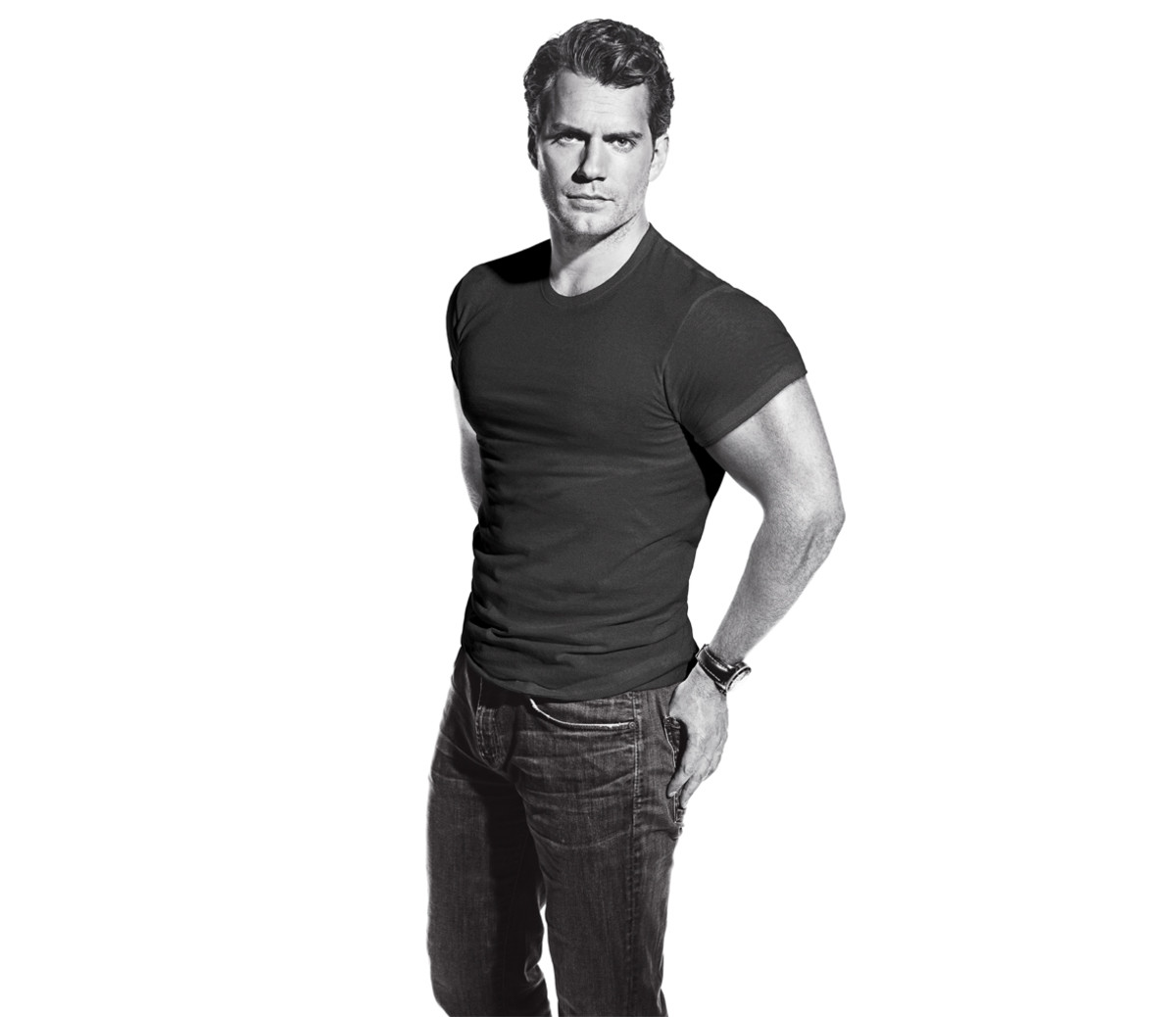

He’s a proper English gentleman who became Hollywood’s all-American badass. But strip away the tights, Savile Row suits, and secret identities, and who is Henry Cavill?

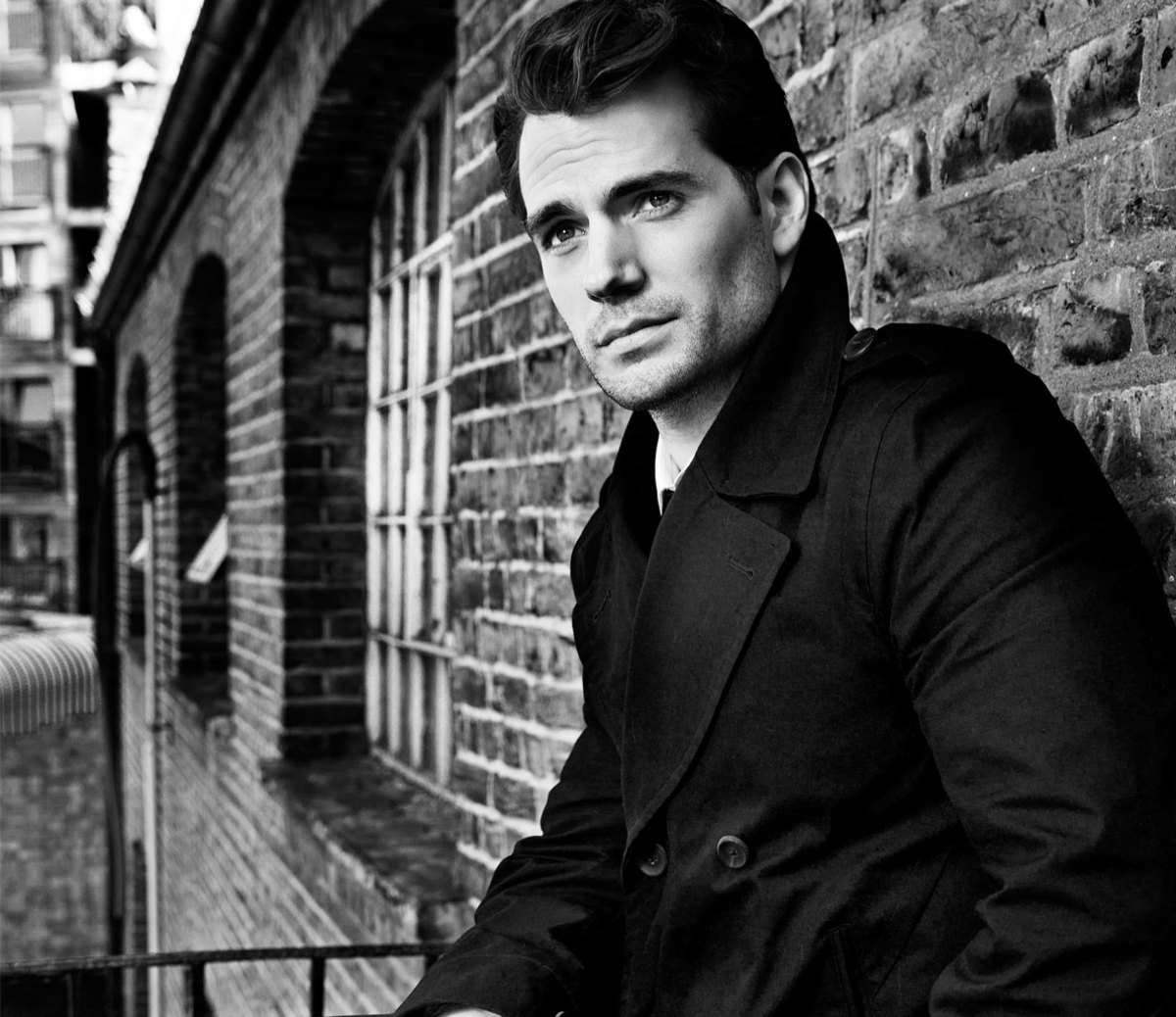

More specifically, I’m having a proper British pint, a golden, glistening glass whose shimmering depths promise all the glory of that most fleeting of moments: the English summertime. It’s a rare sunny day in west London. We’re sitting in the sweltering beer garden of a pub in leafy Twickenham—near where England’s national team plays rugby union, the bone-crunching football-with-no-helmets battle royale often described as “a hooligan’s game played by gentlemen”—and 32-year-old Henry Cavill is drinking his second pint of pilsner top (a pilsner with a dash of lemonade) and radiating contentment.

Cavill is wearing a shapeless dark green Royal Marines hoodie (his brother Nik is a lieutenant colonel who served three tours in Afghanistan and in the invasion of Iraq) and sporting a wildly tangled beard that would guarantee his anonymity had he not spent much of 2013’s blockbuster Man of Steel sporting, well, a wildly tangled beard. But no one bothers him. We are far from Hollywood, in every sense. “If I suggested to an American journalist that we do an interview over a beer,” says Cavill, “they’d find it very weird.” (Full disclosure: I am also British.)

So it came as something of a surprise, back in the U.K. in 2011, when Cavill was cast as the all-American Last Son of Krypton in Man of Steel, director Zack Snyder and producer Christopher Nolan’s dark, controversial take on the Superman origin story, in which Cavill’s carefully controlled moral turmoil suggests that Superman’s true superpower is a stiff upper lip. His compelling performance established Cavill as an A-lister, cementing his spot in next year’s sure-to-be-blockbuster Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, in which he squares off against Ben Affleck’s Dark Knight, and two subsequent ensemble Justice League films, DC Comics’ answer to archrival Marvel’s The Avengers movies.

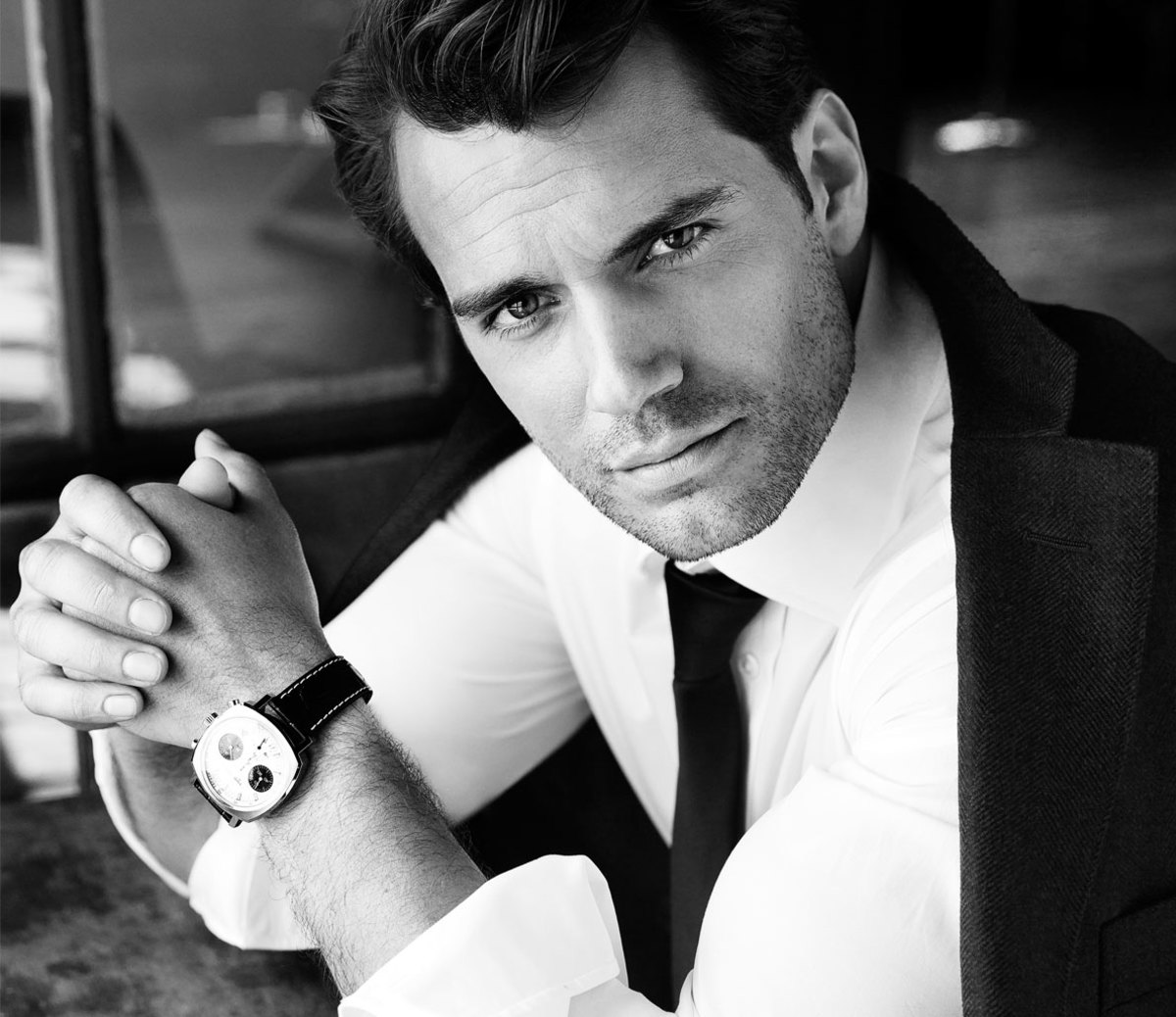

Before all that, however, Cavill appears onscreen as a character who couldn’t be more different from his clean-cut Kal-El. This month he plays the cynical, debonair thief-turned-super-spy Napoleon Solo in The Man fromU.N.C.L.E., director Guy Ritchie’s frenetic reboot of the Cold War TV series. Joyfully unpretentious, the movie is a fast-paced marvel of period production design, like Mad Men, but with fights and car chases instead of pitch meetings and cigarettes. Playing opposite Armie Hammer (the Winklevii in The Social Network and the masked star of The Lone Ranger) as ascetic Soviet hardman Illya Kuryakin, Cavill’s Napoleon is a scoundrel with style. Forget truth, justice, and the American way—Solo is out for himself.

“I thought it was just a really good story, really good fun,” he says. “It was exactly the kind of thing I wanted to do after Man of Steel. Napoleon’s a lot of fun, and he’s probably closer to my own character than Kal-El.” He sips his beer. “Well, a little closer. The key is, Napoleon doesn’t really want to be saving the world. He enjoys the finer things in life, like good suits, wine, fine food. Me, too.

As a stereotypical middle child, Cavill often found himself lost in the family crowd. “I wanted to do right by everyone and follow the rules. Pretty boring, actually!” he says, laughing. “This is probably why I was so unpopular at school, because I was clearly such a wanker.” He corrects himself for American readers. “Sorry: such a douche bag.”

Acting gave Cavill an identity. He appeared in school productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Grease and discovered he had a talent for the stage. “I liked acting, and suddenly people liked me,” he says. “Stowe could have smashed my confidence completely, I think, but actually it prepared me for the world. If I’d gone to Hollywood without having been hurt on a daily basis at school, perhaps I would have been a little less ready for it.”

There was one moment at Stowe that changed everything for Cavill, and it’s so unbelievable it would strain the credibility of even the sappiest of biopics. In 1999, Russell Crowe—who, coincidentally, would play Cavill’s Kryptonian father, Jor-El, in Man of Steel 12 years later—came to Stowe to shoot scenes for the thriller Proof of Life. The 16-year-old Cavill appeared as an extra, running round the rugby pitch in Combined Cadet Force gear. During a lull in shooting, he approached Crowe for advice. What was the business really like

Well, said Crowe, sometimes they treat you really well. Sometimes it’s shit. But the money’s good and you’ll enjoy it. Then shooting resumed. A few days later, Cavill received a care package containing Australian candy, an Aussie rugby jersey, and a CD by Crowe’s band—plus a photo signed with a message: “Dear Henry, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Love, Russell.” Cavill’s still got it. When they met again a decade later on the set of Man of Steel, Crowe remembered the kid from the English boarding school.

“It’s incredible,” says Cavill, apparently still a little dazed. “If you saw it in a film, you wouldn’t believe it happened. But it did.”

Cavill first shot to fame on Showtime’s lurid historical drama The Tudors in the mid-2000s, when viewers got to know not just his face, but most of the rest of him, too. The show was heavy on the sex scenes, especially featuring Cavill’s character, Charles Brandon, Henry VIII’s trusty wingman. No longer fat—in fact, in remarkable shape—Cavill had his chain yanked mercilessly by his brothers over these scenes.

If the role of 007 still requires a shredded physique by then, Cavill’s a shoe-in. In The Tudors he’d been in fine shape. But by the time he appeared as Theseus in Tarsem Singh’s action movie Immortals, in 2011, Cavill was so sculpted he looked as if he’d walked off the set of 300.

“I didn’t go that way for the sake of becoming an action actor,” Cavill explains. “I want to tell stories. That’s what excites me. But there’s a demand that you look a certain way in Hollywood. Man of Steel was the first time I had to